Dating a house can be difficult. Take, for example, the red house at 75 Main Street in Cold Spring Harbor. A sign out front proudly identifies it as “1790 House.” In the 1960s, the building was home to a clothing store called 1790 House; and in the 1980s one could shop at 1790 House Antiques.

Since at least 1953, it has been claimed that the house was built circa 1790. A list of “Old Houses” prepared that year for the Town of Huntington tercentenary, in addition to dating the house to the late eighteenth century, also claims it was the “First place in America where Japanese tea was served.” The audacity of that claim should be enough to foster doubt on the veracity of the claimed construction date.

A State Historic Preservation Office Building-Structure Inventory Form prepared in 1979 dates the building back even further to around 1720. The form states, “This house is believed to be an early house of the Conklin family, early settlers in the valley.” The form cites a 1960 publication written by local Cold Spring Harbor historians, Harriet G. Valentine, Andrus T. Valentine, and Estelle V. Newman. That account doesn’t give a construction date; instead, it says “This house still retains its pre-revolutionary character.”

The Conklin family did have extensive land holdings in Cold Spring Harbor. Richard Conklin (1726-1787) was born in Smithtown. In 1750, he married Rebecca Titus of Cold Spring Harbor. Their son, Richard (1757-1818) was born in Cold Spring Harbor. So, it seems the family had lived in Cold Spring Harbor since the middle of the eighteenth century. However, no deeds transferring land to Richard Conklin, Sr. have been found.

Richard Conklin, Jr. (1757-1818) fought in the American Revolution. After the Battle of Long Island in August 1776, he fled to New England. At one point, he was held as a prisoner on a ship in New York Harbor. He escaped and made his way back to his home in Cold Spring Harbor. His return was reported to the British, who “attacked the house, firing through the barred door, where he stood until the rest of the family had escaped to a neighbor’s. He then retreated through a swamp and the woods to the shore where his vessel lay.” (Mather’s Refugees of 1776 from Long Island, page 306). That description of escaping through a swamp is consistent with his house being located at 75 Main Street because the area to the north along today’s Spring Street could be described as swampy.

In 1782, Richard, Jr. married Mary Bernard from North Carolina. After the war, he returned to Cold Spring Harbor where he was a seaman. In the nineteenth century, his home, known as Evergreen House, was on Harbor Road, near Portland Place, approximately where the old motel is now located. He may have built this house around the time he married because when it burned down in 1899, it was described as being a hundred years old. It could be possible then that 75 Main Street was the Conklin homestead prior to the Evergreen House.

As for determining when that house was built, there are several ways to date a building in the absence of building permits, which were not required in Huntington until 1934. One can consider the style of the building, construction methods, materials, and documentary sources. Nineteenth century Long Islanders tending to be somewhat conservative when it came to architecture, being slow to adopt new styles. As a result, older forms continued here well after other regions had moved on.

The house at 75 Main Street incorporates some features of the Greek Revival style that became popular starting around 1820. The house features a simple cornice with returns, garrison windows and narrow sidelights around the entry. On the other hand, hand hewn beams visible in the west section of the house and the house’s narrow, tapered newel post point to an eighteenth-century construction date.

However, unused mortises on the hand-hewn beams indicate that they may have been recycled from an earlier building (other beams are milled) and the narrow newel post on the stairs is consist with a 1790 construction date as well as a later date. The foundation is rubble stone topped with several courses of brick. Use of bricks in a foundation points to a nineteenth century construction date.

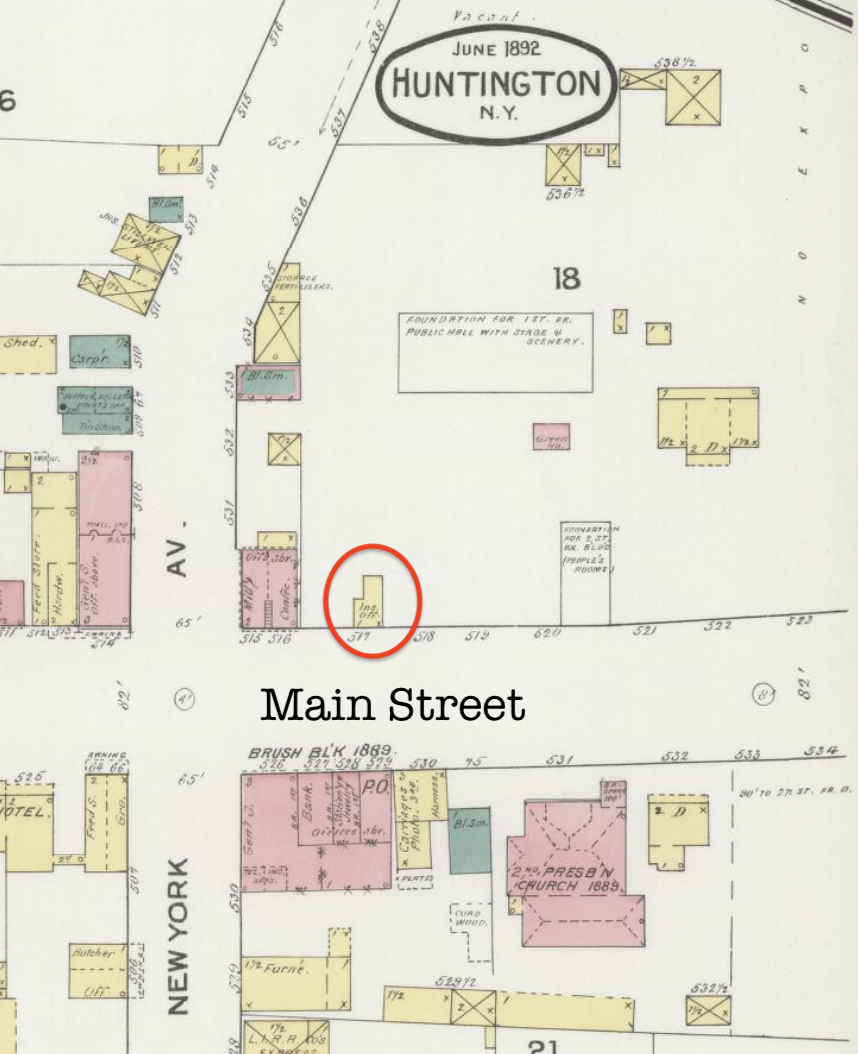

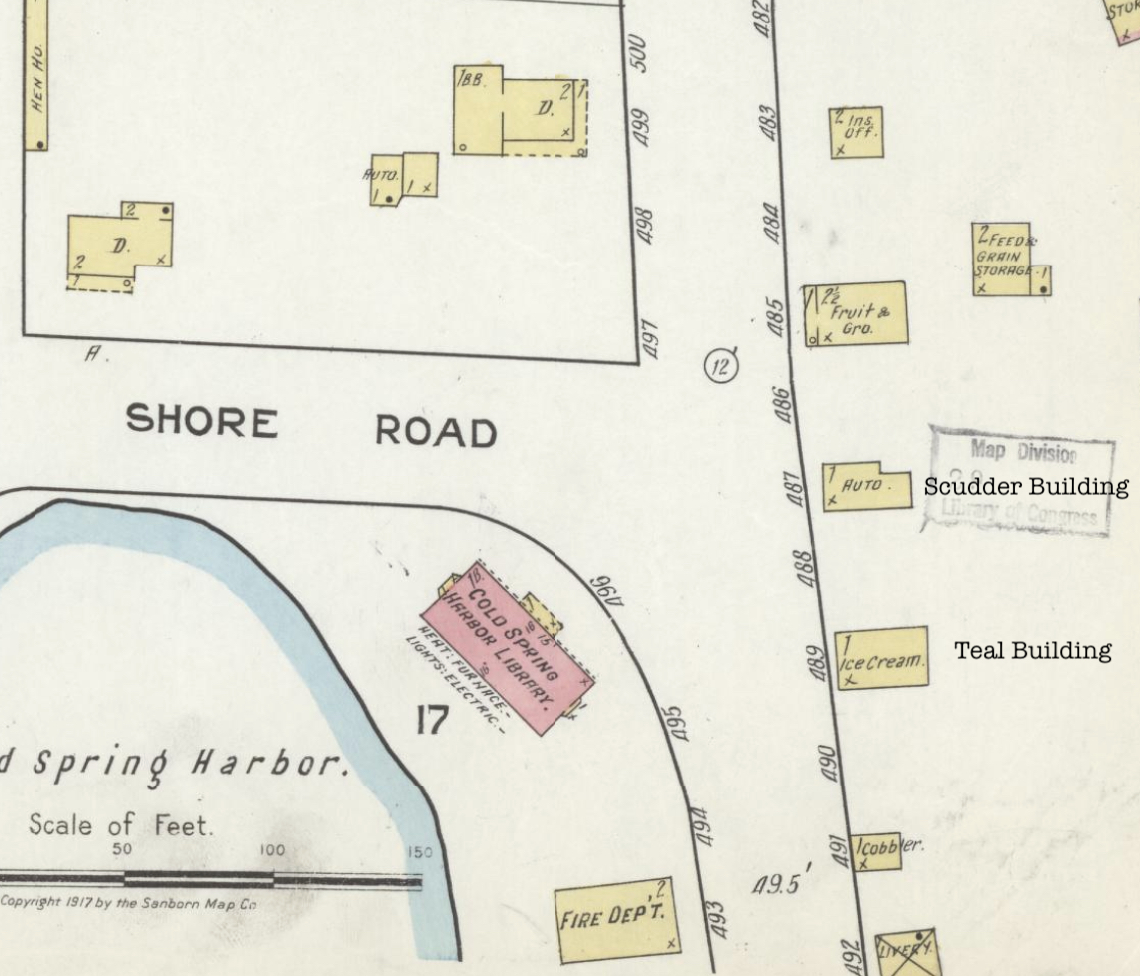

Another piece of evidence is the deed for the property. Richard M. Conklin, son of Richard, Jr., sold the 70’ x 100’ lot on which the house sits to Israel Valentine, a carpenter from Oyster Bay, on Leap Day 1836. This seems to have been only the second sale of land on Main Street—two months earlier Conklin sold the lot to the west to Abraham Walters. Most telling is a restriction in the Valentine deed that “any house to be erected shall range in front with those lately erected by Richard M. Conklin and Abraham Walters and no building erected shall be nearer to the said highway.” If the house already existed, there would be no reason to include this restriction. In addition, according to the deed, the property consisted of two 35’ lots. If there was a building on the property, why create a lot line running through it?

While one hesitates to contradict a widely accepted 70-year-old claim, it seems possible that the house was built by Israel Valentine in 1836, rather than by the Conklin family in the eighteenth century.

While the age of this building may be uncertain, its history after 1840 is clearer. That was the year that Samuel M. Sutton acquired the property from Israel Valentine. The 1850 census lists Sutton’s occupation as Stage Proprietor. His household included his wife and daughter as well as a physician, a tailor (and his wife and son), a laborer, and an Irish immigrant whose occupation was not given. The number of non-relatives would be consistent with running a hotel. According to an account from 1903, in 1841 Sutton kept the only hotel in Cold Spring Harbor.

Local Temperance Society members were unhappy that Sutton served liquor in his hotel. In 1841, they organized a march from Huntington village to Sutton’s hotel to destroy his liquor. It appeared Sutton saw the error of his ways. The Temperance Society offered to buy his stock of liquor and he agreed to sell. The Temperance Society members debated whether to pour the liquor into the harbor or burn it in the middle of Main Street. The fire crowd won the argument. Barrels were stacked in the middle of the street and put to the flame. Only the flammable liquor did not ignite. It turns out Sutton had replaced the liquor with water. What he did with the liquor is unknown.

But despite his duplicity, Sutton must have reformed because by the following March, the Washington Benevolent Temperance Society of Cold Spring Harbor was meeting at “Sutton’s Temperance Hotel.”

Three weeks before he died in January 1855, Sutton sold 75 Main Street to Ezra W. Seaman. In 1850, Ezra lived with Noah Seaman, who may have been his uncle. On the 1850 census, Noah was identified as “Hotel Keeper;” Ezra is listed as a “Merchant.” That is consistent with an article from 1851 reporting that “The store of Noah Seaman, at Cold Spring, L.I., occupied by Ezra Seaman as a Dry Goods and Grocery store, was consumed by fire on Saturday night last.” Noah Seaman’s house as well as store and dock were located on Harbor Road where the dirt parking lot is now located—just south of the Conklin’s Evergreen House.

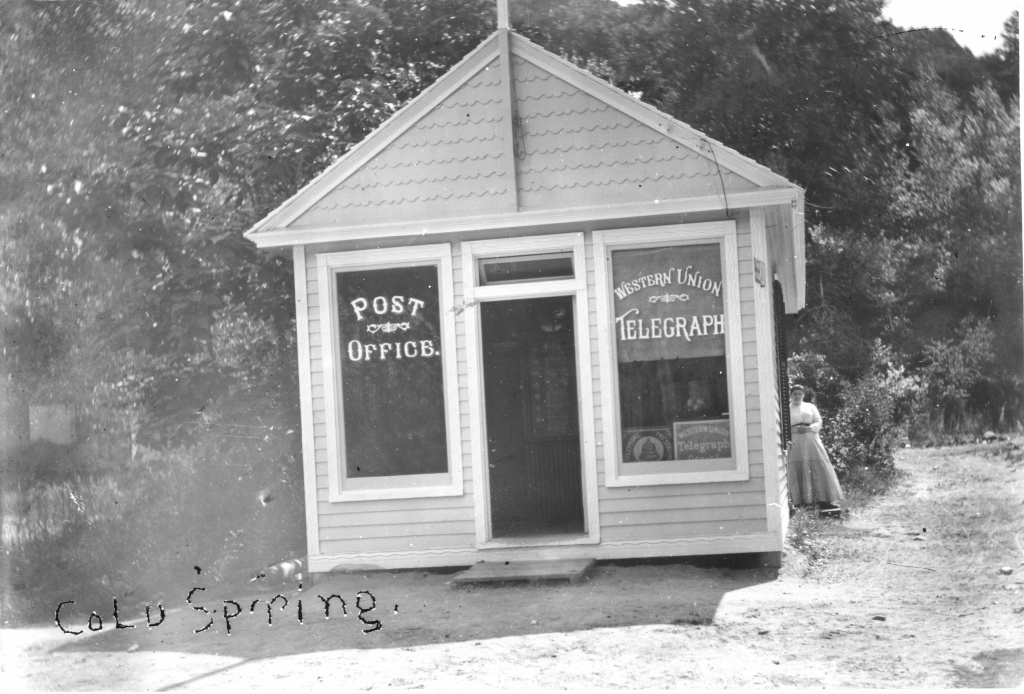

Three years after the fire, Ezra purchased the property at 75 Main Street. On the 1858 map of Suffolk County, the building is identified as “E.W. Seaman Rail Road House.” The name is puzzling because at the time, the Long Island Rail Road only reached as far as Syosset. But living in Seaman’s Rail Road House was 40-year-old Calvin Conklin, who was Black and was employed as a Stage Driver. Presumably, he drove a coach to Syosset to meet the trains, thus justifying the hotel’s name.

In addition to running the hotel, Seaman, like his father, was a miller and managed the Jones flour and grist mill on Harbor Road. In 1855, Seaman married Delia C. Smith. Ezra and his brother-in-law Thomas A. Smith ran the Suffolk Hotel during the Civil War. After retiring from the hotel business, he “engaged in the grocery and butcher business at Cold Spring” according to his obituary.

Seaman mortgaged the property three times. First in 1855, when he purchased the property, he gave a mortgage to Andrew Valentine (son of Israel Valentine). Three months later, he borrowed money from his neighbor Abram L. Holmes. Finally, in 1861, he borrowed money from his father. A notice of a mortgage sale dated March 8, 1864 was published in The Long-Islander by Andrew K. Valentine in an action against Ezra W. Seaman and others. The genesis of that action appears to have been a default on the mortgage to Andrew Valentine. There are a dozen defendants named in the suit: Ezra W Seaman, Delia C. Seaman, his wife, Abraham Holmes, Lewis Seaman, John W Smith, Willet Robins, Stephen R Post, Samuel Van Wyck, John A. Ruso, Jr, Lawrence Drumgold(?), Wm D. Jones, and Samuel S. Jones. The connection of many of those defendants to the property is unknown, but the first named were the debtor and subsequent lenders. The court in Brooklyn ordered the sale of the property at auction. Andrew K. Valentine was the highest bidder at $2,100. (Liber 126, page 585, May 3, 1864.)

According to his obituary (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 3, 1901, p 14,) Seaman moved to the South Shore in 1873. His sister, Mary Lucas Buckingham, lived in Cold Spring Harbor at the time of Ezra’s death. Mary Lucas had married William Harmon Buckingham and had one daughter, Lucy, who married William T. Lockwood, the son of James H. Lockwood of 117 Main Street.

In the early twentieth century, the Buckinghams and Lockwoods occupied this building as a double house. William Buckingham, who died in 1907 was a ship-joiner who had worked in 1858 on the Panama railroad (The Long-Islander, January 4, 1906, page 7). His son-in-law, William T. Lockwood continued his father’s grocery store at 117 Main Street.

According to a history of Cold Spring Harbor by Leslie Peckham, in the early twentieth century, a Chinese laundry operated from a small building between this building and the house to the west. There were two Chinese workers in the laundry who wore traditional Chinese garb and spoken very little English.

By 1960, the house was owned by Edward Hewitt and was home to two shops and law offices. In subsequent years, it was and continues to be, the location of various stores and offices—but has long since ceased to be a hotel.