In just over two years, the United States will celebrate the 250th anniversary of its independence. It may seem that a country settled in part by people calling themselves Separatists was destined to be independent. While the roots of independence can be found in the country’s earliest English settlement, the actual reality of independence was slow to develop. Certainly in 1774, Americans considered themselves to be very much a part of the British empire.

A central question that gave rise to the Declaration of Independence in July 1776 was whether Parliament had the authority to tax the colonies. The question became more urgent in the aftermath of the Seven Years War (1756-63), also known as the French and Indian War, as parliament sought to raise revenue to help pay war debts.

The first effort, the Stamp Act of 1765, was short lived being repealed in 1766. It was followed by the Townsend Act of 1767, which imposed a tax on British china, glass, lead, paint, paper and tea imported to the colonies. The colonists boycotted these goods and eventually the taxes were repealed with the exception of the tax on tea. Colonist, who were among the biggest drinkers of tea in the world, often consumed smuggled tea, but purchased taxed tea as well.

The Tea Act of 1773 was passed to help the struggling Britain’s East India Company. The company would no longer be required to sell its tea at auction in England. It could now ship tea directly to consignees in the American colonies, thereby saving the customs duties when the tea was conveyed through English markets. The three pence a pound tax upon import to the colonies was continued. Taxed tea sold for 2 shillings a pound (including the 15% tax) and would now be competitively priced in relation to smuggled tea, even a bit less expensive than smuggled tea.

However, for both Britain and the colonies, it wasn’t the money. It was the principle. Parliament wanted to assert its authority to impose taxes on is colonial subjects. The Americans were just as adamant that they should not be taxed by a body in which they had no representatives.

This refusal to pay the tax led to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773. Rather than accept delivery of the tea and pay the tax, Bostonians dumped the tea in the harbor. In response to the Bostonians’ defiance, Parliament passed what came to be known in America as the Intolerable Acts, which among other things, shut down the Port of Boston until the damaged tea was paid for.

Samuel Adams, a leader of the Sons of Liberty in Boston, called for a continental congress to develop a unified colonial response. Others called for a boycott of British goods. News of the Boston Port Act reached Manhattan on May 11, 1774; it probably reached Huntington a week or two later.

While support for Boston varied throughout the colonies, Huntingtonians were unambiguous in their support for their neighbors to the north. Huntington declared “that our brethren of Boston are now suffering in the common cause of British America.” That common cause was to fight taxation without representation.

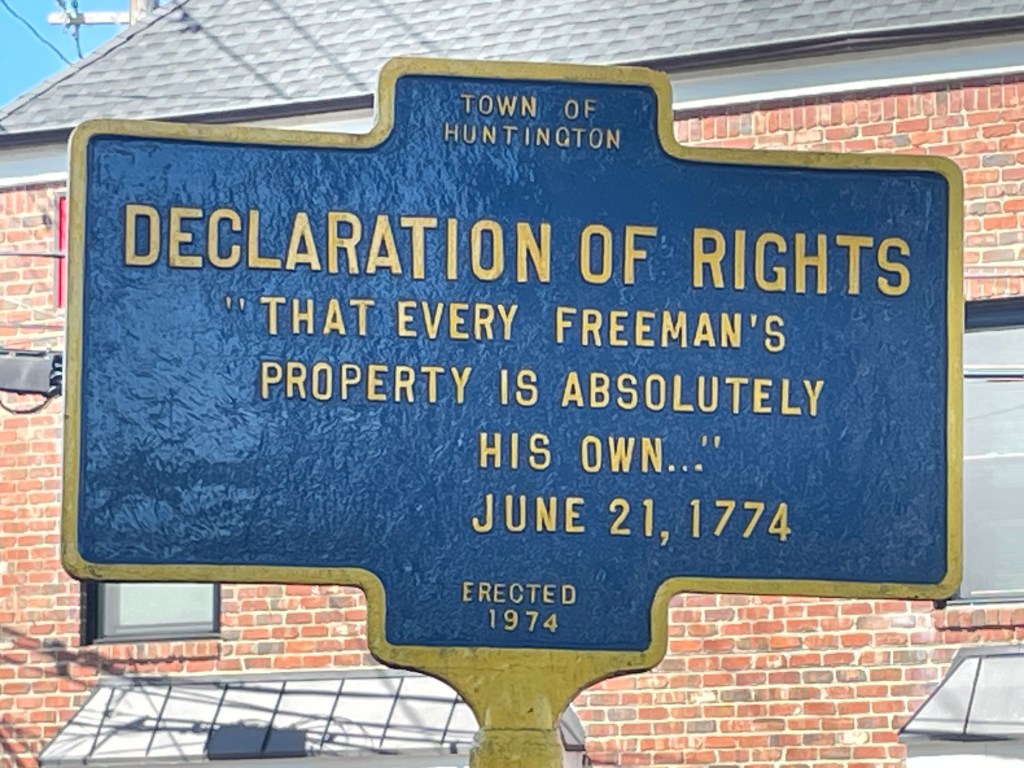

On June 21, 1774, Huntington adopted its Declaration of Rights asserting that “every freemans (sic) property is absolutely his own, and no man has a right to take it from him without his consent, expressed by himself or his representatives.” Therefore, without representation in Parliament, the colonies could not be taxed by that body.

This view was long held by Huntington’s residents. As early as 1670, six years after the Duke of York asserted control of Long Island, the townspeople refused to comply with an order to help repair the fort in Manhattan in part because “wee conceve wee are Deprived of the liberties of english men.”[1] The English had promised a Colonial Assembly with delegates elected by the people. Since the Assembly no longer met by 1670, the tax imposed by the Royal Governor amounted to taxation without presentation. Likewise, in July 1691, the Town adopted an oath that no tax shall be imposed except by act and consent of the governor, council and “Representatives of ye people.”[2]

The views expressed in Huntington’s Declaration of Rights were also consistent with the resolutions eventually adopted by the First Continental Congress which met in Philadelphia from September 5 through October 26, 1774. The first resolution adopted by the Congress was “That the inhabitants of the English Colonies in North America, by the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English Constitution, and the several Charters or Compacts, have the following Rights: . . . That they are entitled to life, liberty, and property, and they have never ceded to any sovereign power whatever a right to dispose of either without their consent.”

Other towns throughout New England, including on Long Island, adopted similar resolutions. A week before Huntingtonians met, residents of South Haven (i.e., the southern section of Brookhaven Town) adopted resolutions declaring the blocking of the port of Boston to be unconstitutional and that the colonies should adhere to a non-importation agreement. Likewise, on June 17 East Hampton pledged to support their fellow colonists and to participate in a non-importation agreement. The resolutions adopted by these Towns did not spell out citizen’s rights as completely as Huntington did. On August 9, Smithtown adopted the Huntington resolutions. In November, the Committees of Correspondence of Suffolk County voted their full approval of the Continental Congress.[3]

The following May, two weeks after the Battles of Lexington & Concord, Huntingtonians voted “that there should be eighty men chosen to Exercise and be ready to March.”[4] The tenor of the conversation had changed.

Although in his Centennial Address delivered on July 4, 1876, the Honorable Henry C. Platt deemed the Declaration of Rights to be “Huntington’s DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE,”[5] this is clearly a misreading of the document. There is no mention of independence, just an assertion of rights as citizens of the British Empire. The full text of the Declaration of Rights appears below. Although the author is unknown, it is thought that it was written by John Sloss Hobart, Lord of the Manor of Eaton, because he had legal training. He served as a representative to the New York Provincial Congress and after the war was a judge and U.S. Senator.

(1774, June 21,)

1st That every freemans (sic) property is absolutely his own, and no man has a right to take it from him without his consent, expressed by himself or his representatives.

2nd That therefore all taxes and duties imposed on His Majesties subjects in the American colonies by the authority of Parliament are wholly unconstitutional and a plain violation of the most essential rights of British subjects.

3rd That the act of Parliament lately passed for shutting up the Port of Boston, or any other means or device under color of law, to compel them or any other of His Majestys (sic) American subjects to submit to Parliamentary taxation are subversive of their just and constitutional liberty.

4th That we are of opinion that our brethren of Boston are now suffering in the common cause of British America.

5th That therefore it is the indispensable duty of all colonies to unite in some effectual measures to the repeal of said act and every other act of Parliament whereby they are taxed for raising a revenue.

6th That it is the opinion of this meeting that the most effectual means for obtaining a speedy repeal of said acts will be to break off all commercial intercourse with Great Britain, Ireland and the English West India colonies.

7th And we hereby declare ourselves ready to enter into these or such other measures as shall be agreed upon by a general congress of all the colonies: and we recommend to the general congress to take such measures as shall be most effectatl (sic) to prevent such goods as are at present in America from being raised to an extravagant price.

And lastly we appoint Colonel Platt Conkling, John Sloss Hobart Esq. and Thomas Wickes a committee for this town, to act in conjunction with the committee of the other town in the county, as a general committee for the county, to correspond with the committee of New York.

ISRAEL WOOD, President

[1] Huntington Town Records, Vol I, page 163

[2] Huntington Town Records, Vol II, page 93

[3] “Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties,” by Henry Onderdonk, Jr. (1849), pages 13-16

[4] Huntington Town Records, Vol. II, page 537

[5] “Old Times in Huntington, An Historical Address by Hon. Henry C. Platt, Delivered at the Centennial Celebration at Huntington, Suffolk County NY on the 4th day of July, 1876, page 19

Always learn something new when I read your articles.

Thanks Robert

Betty

I found out that my 7X or so Great Grandfather was indeed Thomas Wickes of Huntington, NY. His son Thomas Jr. Wickes 1650-1726 was married to Deborah Wood. his father was Thomas Weeks 1612-1671 married to Isabella Elizabeth Harrcutt. Thomas Wickes was one of the signers of the Declaration of Rights. My 1st cousin once removed from New Albany, Indiana put a Wickes Allen copy of our Wickes and Platt heritage ancestry in the historical society of Huntington back in 1980. Our 2x great grandfather that moved to New Albany, Indiana was named Joseph Lewis Wickes or Wicks. His daughters and grandchildren girls were all charter members of the Floyd Co. DAR there in Indiana. We have a great grandfather last name Platt as well. Several Patriots are in that line of Wickes family. Platt Wicks married a Susanna Raymond. Her father was the patriot. Simeon Raymond and son Nathaniel Raymond.

This is from the booklet published by the Huntington, New York Historian, “A Brief History of The Arsenal”:

“The land upon which the Arsenal stands was originally part of the homelot granted to William Rogers when the town was laid out in 1653. After a succession of owners, it was bought by Thomas Wicks, Jr. (one of my great grandfathers). who lived next door on the land now occupied by the Village Green School. Wicks spent many years buying up adjacent parcels from his neighbors and eventually expanded his original six-acre homlot to the fifty-five acres.”

“Thomas Wicks, Jr. deeded the property to his son Joseph Wicks in 1714, but retained rights to sole us until he died. Thomas died in 1726, and Joseph became the clear owner of the property.” Physical examination of the Arsenal has revealed that the original part of it was built during the ownership of Joseph Wicks, and not before. It was probably built around 1740 as a farm building, for the storage of grain. Joseph Wicks died in 1740 and the property was inherited by his son, Joseph Thomas Wicks, Jr. Joseph sold the building with one and one-half acres to Gershom Sexton. Sexton died in 1751, and the property went back to Joseph Wicks, who sold it again to a Job Sammis.

Sept 14, 1775 the New York Provincial Congress shipped one hundred pounds of powder to Ebenezer Platt for use of the troops. When it arrived, it was turned over to Job Sammis and was eventually issued to the troops from his house, the Arsenal.

On January 5, 1776, the Provincial Congress sent a thousand pounds of gun powder to the Arsenal, for use by the militiamen.

July 1776 British landed at Staten Island to invade New York. First to arrive at the Arsenal were Capt. Thomas Wicks with his company, and Capt. Gilbert Carrl with his company.

So amazing to actually find the Arsenal I have read about in our 1980 family history since I was 12 years old. Phil Jackson Wilmore, KY pdjackson550@gmail.com.