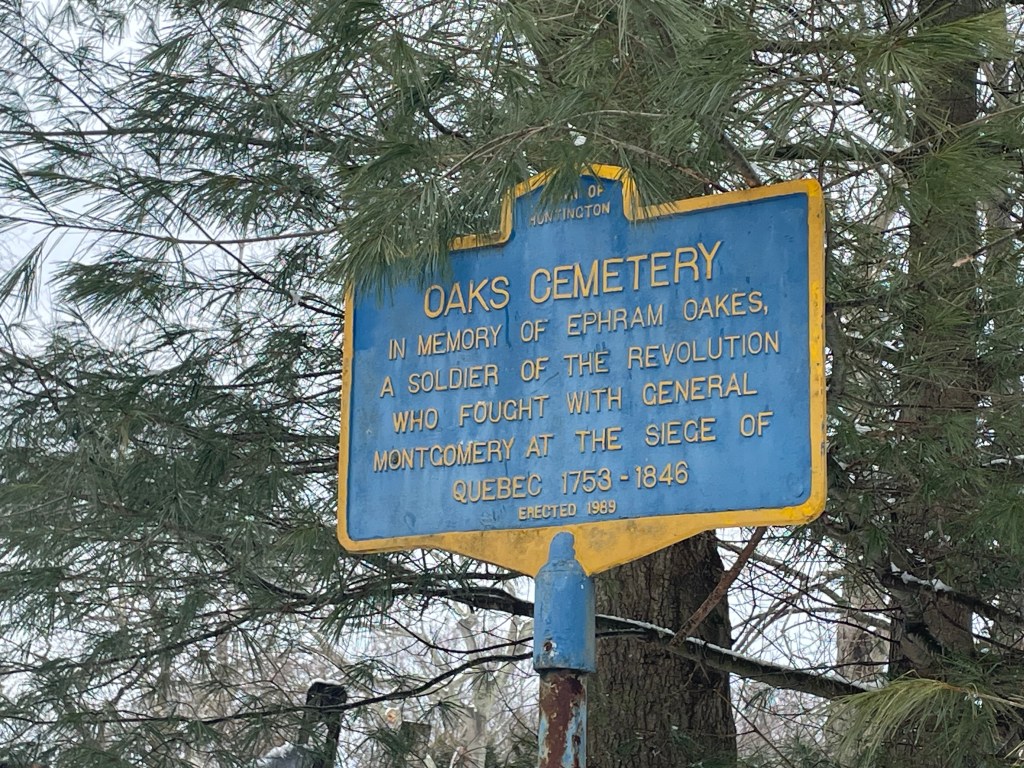

A century ago, a thirst for water led to the formation of the village of Huntington Bay in the East Neck section of Huntington.

In 1923, residents of East Neck joined with other Huntingtonians to petition for a municipal water district covering the territory from Huntington Bay to Jericho Turnpike. Seemingly having second thoughts about the expense of a water district in which they would probably bear the greatest financial burden, a second petition was circulated among the wealthy residents of East Neck to incorporate the area as a separate village. This was necessarily a novel concept. Twelve years earlier residents angered by the condition of roads in the area, the lack of street lights, and the need for better water supply met to discuss incorporation. They pointed out that only about 10% of the money paid Huntington Bay residents for highways was spent in their area. East Shore Road in front of St Andrews by the Sea chapel was so flooded that boys would sail boats on it. However, after meeting with the Town Supervisor and Superintendent of Highways, where complaints about the condition of area roads dominated, the residents were mollified. (Brooklyn Eagle, September 23, 192, page 10; The Long-Islander, September 27 and October 4, 1912).

Under State law, a municipal water district could not include a separate municipality within its borders. The incorporation petition, signed by 36 residents, was filed before the petition for the new water district. A vote on incorporation was held on February 4, 1924 and was approved 29-10. Subsequent village elections typically attracted only about two dozen voters.

The first meeting of the Board of Trustees of the new village was held on March 12 at the Transportation Club in Manhattan. William J. Taylor was elected president; and George Adamson and Mansfield Snevily were elected trustees.

The first ordinance, covering streets and roads, motor vehicle, sewage, swimming and bathing, and landing of boats was adopted on April 1. Most village functions focused on improving roads. In the first year, sixty percent of the village budget was dedicated to road maintenance and improvement. Within just two years, the village also saw the subdivision of its two large estates into residential neighborhoods with a more suburban layout, Wincoma and Bay Hills.

Early meetings of the trustees of the Incorporated Village of Huntington Bay were held in Manhattan because many of the trustees and villagers had their primary residence in Manhattan or Brooklyn. Still, they recognized a need for a Village Hall. In June 1925, the trustees agreed to purchase land from the Halesite Company for that purpose. The new Village Hall, described by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as “one of the prettiest little municipal buildings in one of the smallest incorporated villages in the State,” opened in the summer of 1926.

The new village included several distinct tracts of land that had been farmland, then became estates for city residents and finally were subdivided into the neighborhoods we know today. Through the centuries, these distinct tracts have remained easily identifiable. Below is a brief history of those tracts.

Bay Crest

Willett Bronson, the son of a wealthy doctor, was East Neck’s first land speculator. For generations, land in East Neck had been farmed by early Huntington families. Later wealthy New Yorkers, looking to escape the calamities of city life, purchased large tracts to serve as their country homesteads. When Bronson purchased the sixty acres that would become known as Bay Crest, it is unclear if he intended to use the land as a summer retreat or if he intended to subdivide it into “villa lots” where wealthy New Yorkers could erect summer cottages, which is what he eventually did.

Bay Crest was not Bronson’s first foray into real estate development. Bronson was born in Hudson, NY in 1840. His grandfather, Isaac Bronson, served as a surgeon during the American Revolution. After the war he gave up the practice of medicine and along with his son Arthur founded the New York Life Insurance and Trust Company, which pioneered the use of life insurance and in 1822 merged with the Bank of New York, and Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, the collapse of which led to the Panic of 1857. Isaac Bronson became one of the wealthiest men in New York City and purchased vast tracts of land in several states.

Willett Bronson served in Company F of the New York 7th Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. After the war, he studied law, but it is unclear if he pursued a legal career. When his father died in 1875, Bronson inherited a large fortune. Using his inherited wealth, he soon became engaged in real estate speculation in Manhattan.

Bronson had a home in Huntington village by 1877. The home on New York Avenue was considered one of the showplaces of the village.[i] By 1880, Bronson was offering building lots on land between New York Avenue and Nassau Road along a new road known as Hudson Avenue.[ii] Although it appears that the new road was laid out and fences erected along its sides, today there is no Hudson Avenue running between New York Avenue and Nassau Road; nor does it appear on any of the early maps. Earlier the property had been owned by Stephen C. Rogers and by 1891, it was described as being “lately owned by Willet Bronson.”[iii] In 1894, it was sold to Mary Cantrell,[iv] whose son in 1910 subdivided the property under the name Villa View Heights—the area surrounding Central Parkway.

In 1882, Bronson purchased sixty acres between Bay Avenue and Huntington Bay from former Congressman William Roberts.[v] Unfortunately, soon after he purchased the land, the 45-year-old house on the property burned to the ground. But he quickly rebuilt. [vi]

Bronson’s misfortune soon extended to his Manhattan real estate holdings. Bronson had borrowed heavily to develop his holdings. He also made building loans to developers building on speculation without knowing enough about the business himself. In 1883, he and the builder with whom he worked to develop properties on the East Side had a falling out. Bronson was unable to cover the payments on the money he had borrowed and by December had to make assignments for the benefit of his creditors. Poor management and bad advice were blamed. He had invested a million dollars, and after some initial success, it was claimed that he got in over his head.[vii]

How, or if, his misfortune in Manhattan real estate effected his Huntington holdings is unknown. Perhaps he had purchased the land in East Neck as a country seat as so many wealthy New Yorkers before him had done. There is certainly enough evidence that Bronson had strong connections to Huntington. He was actively involved with St John’s Church, serving as a vestryman and hosting fund raising teas at his East Neck property. In both the 1880 and 1900 censuses he is enumerated as living in Huntington. Finally, perhaps the best evidence of his intention to make Huntington his home rather than just a place to invest is the fact that both he and his wife are buried at Huntington Rural Cemetery.

Whatever his original intentions were, just a month after assigning his Manhattan properties, Bronson hired local surveyor Oscar Darling to prepare a plan dividing the East Neck property into building lots.[viii] The result was a plan for 11 building lots from 3 to 6 acres each and 11 small beach lots. In October 1886, it was announced that three men from New Jersey would be purchasing a considerable portion of the Bronson property.[ix] James B. Dill purchased two building lots and two beach lots on the west side of Beach Avenue. Albert W. Palmer purchased the building lot on the east side of Beach Avenue and his father, also Albert, purchased the adjoining lot to the east. The Palmers also purchased the two eastern most beach lots.[x] Three months later, Albert Palmer purchased the 90-acre Moses Jarvis farm.[xi]

Dill and the Palmers were neighbors in East Orange, NJ, and their wives were sisters. When he purchased property in Bay Crest, Dill was a young lawyer just starting to concentrate on corporate law. He later would write the New Jersey’s Corporation law and establish the Corporation Trust Company, which profited from the new law. In 1905, he was appointed as a judge on New Jersey’s highest court.

Albert W. Palmer was the head of Albert Palmer & Co, a publishing firm that printed trade publications. He had assumed control of the company when his father retired in 1883. Palmer and Dill were both in their early thirties when they came to Huntington. Dill had rented a house on Fairview Street the summer before his big purchase. The sale was hailed as “some of the most important transactions that have taken place in this town for some time.”[xii] The purchasers promised to erect houses costing not less than $6,000 by the end of the next summer. And, in fact, by the following February construction had begun. It was anticipated that the construction would mark a new era in Huntington “and that the ‘boom’ will not stop until every one of the beautiful hills about the village are crowned with scores of handsome residences.”[xiii]

Dill and Palmer also planned to build a club house with hotel accommodations for 40 to 50 guests. They planned to subdivide the Moses Jarvis property into villa plots.[xiv]

The year after the sale to Dill and Palmer, Bronson subdivided his remaining property into 22 smaller lots and named his subdivision “Bay Crest.”[xv] He retained about 15 acres in the southwest corner of the property for himself. But in 1896, this piece too was further divided into 24 lots.[xvi] Bronson continued to spend summers in Huntington and sold off additional lots. He also rented furnished cottages for the summer season. In 1901, a ten-room cottage with all the modern conveniences, an unsurpassed view and private beach and bathing house rented for $400 for the season (about $15,000 in 2024 dollars).

The Huntington Company & Hale Site

A little over a year after Dill and Palmer purchased lots in Bay Crest as individuals, a new company was formed to make substantially larger purchases. The Huntington Company was incorporated in February 1888 “to lay out and subdivide lands into building lots and villa plots, to improve and sell the same and erect buildings thereon.”[xvii] Dill was one of the trustees. The others were John W. Aitken and George Taylor. Aitken was the senior partner in the firm of Aitken Sons & Co, Inc., a high-end clothing store started by his father in 1835.[xviii] George Taylor was the president of Aitken Sons & Co.

The company purchased a substantial amount of land in East Neck starting with 53 acres of the Titus Conklin Farm, which bordered Bay Crest to the east.[xix] Titus Conklin had acquired the farm from the estate of Stephen V. Hendrickson in 1838.[xx] His son, also Titus, and daughter Lucinda continued to live in the farmhouse on the west side of Vineyard Road after they sold the farmland east of Vineyard Road to the Huntington Company.

Plans were made for a public water supply, proper drainage and sewerage, electricity and even telephone service to New York. The company purchase land in Huntington Station on which to build a barn and stables to accommodate residents’ horses and carriages while the owners were in the city.[xxi] The company also provided livery service to the train depot via a large four horse stage with a driver and two footmen.[xxii]

The Company applied for a lease from the Town’s Board of Trustees of the underwater land in front of its property—in order to exclude excursions from the city or “roughs” from landing on its beach. [xxiii]

Dozens of men were hired to clear the land and build cottages with expansive views. By 1889, the Company offered villa sites and cottages for sale and also for rental for the summer season. Inducements included a complete water and sewerage system; excellent inland and shore front drives; and the finest sailing, bathing and fishing. Houses came with modern conveniences such as hot and cold water, bath, and water closets.[xxiv]

The project was met with enthusiasm. The Long-Islander claimed that the “property [was] unsurpassed by anything on the Island, or, for that matter, anything within 100 miles of New York City. With high rolling ground, affording land and water views, most striking in form, successfully rivaling the world-famous views of the Bay of Naples, it only needs seeing, to convert the most skeptical as to the beauty and desirability of our town as a place of residence.”[xxv] A couple of weeks later, the paper asserted that “The improvements, which they are placing here, are permanent and of a right character and are to be occupied by parties who will naturally fall in with the town and are likely to become permanent residents.”

Likewise, The Brooklyn Eagle remarked that Huntington “is particularly favored in the class of people that make it their home. The absence of cheap hotels and boarding houses prevents an influx of undesirable summer people. All this is appreciated by the people of the better class, who are naturally drawn to such a locality.”[xxvi]

Summer visitors were attracted to “one of the loveliest spots on earth, a very garden of Eden. It has been so improved as to abound in fine drives and shaded roadways. Sweet bits of landscape and magnificent water views are on all sides. … From the bay the land rises gradually to the table land. The inland drives over good roads are invariably delightful. The views of the harbor, bay and sound as obtained from the hills miles away is one long to be remembered.” And, of course, “The absolute freedom from malaria and mosquitoes, the unexcelled still water bathing, making the fine anchorage for yachts, all tend to make it popular.”[xxvii]

Although Dill was credited with “discovering” East Neck, George Taylor became the driving force behind the Huntington Company’s efforts. It is difficult to untangle the inter-relationships among the investors and the company, which often led to inaccurate reports of who was making a particular land purchase. For example, in its May 19, 1888 edition, The Long-Islander reported that The Huntington Company had purchased the 55-acre farm of Frederick G. Sammis and that the farm “will afford room for a whole avenue of handsome villa plots and building sites.” In fact, the land was purchased by George Shaw, whose connection to The Huntington Company is unknown, but who was a partner in Aitken Sons & Company and that company’s European buyer. The dry goods merchant seems to be a common denominator among many of the players behind the development of East Neck. Shaw did not develop the farm into villa plots. However, the old farmhouse was converted into a hotel known as the Huntington Bay Inn. The Inn was discontinued three years later.[xxviii]

Within a few years, Taylor purchased most of the Company’s land. By the turn of the century, Taylor owned half a dozen cottages that he would rent for the summer season. Taylor was enamored by an earlier visitor to East Neck—Nathan Hale. Nathan Hale began his spying mission for George Washington on the shores of Huntington Bay in September 1776. Although the question is in dispute, it has long been believed that he was also captured in the area a few days later. In any event, in 1894 Huntingtonians memorialized the town’s connection with the country’s first spy by dedicating a memorial to the patriot outside the public library on Main Street in Huntington village. The plans also called for a granite boulder to be moved to the beach to mark the spot where Hale landed. Taylor completed that part of the plan three years later when he had a large boulder moved from the back of his house to the beach. For more , see Nathan Hale Memorials

Taylor’s devotion to Nathan Hale extended to the naming of his estate. He christened the estate Hale Site. When local residents petitioned the postal service for a local post office in 1899, the estate’s name was condensed to one word.

Beaux Arts Park

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Huntington was as popular a place for a summer vacation as the Hamptons are today. An epicenter of the Huntington summer resort scene was at East Neck. Starting in the 1870s, summer visitors could avail themselves of a waterfront inn established by the famous and colorful, bare-knuckle, bantamweight boxer and Brooklyn saloonkeeper William Clark on the shores overlooking Huntington Bay.

In 1891, the property was sold to Nelson May, who was connected with the Huntington Company, the firm that had developed summer cottages in Hale Site, just west of the hotel property. After the old hotel burned down, May built a larger hotel. In 1906, May sold his hotel and the 50-acres it sat on to three of the Bustanoby brothers who planned to create a Long Island compliment to their successful midtown restaurant, Café Des Beaux Arts.

The hotel was renamed the Chateau des Beaux Arts, and the brothers hired the prestigious architectural firm of Delano and Aldrich to design a waterfront casino in the beaux-arts style that would accommodate diners at the water’s edge with broad terraces and a rooftop garden. A long pier extended into the bay to accommodate yachts of any size.

When it opened, the Chateau des Beaux Arts was a hit. The brothers soon announced plans to develop the property beyond the hotel and casino. They hired local surveyor Conrad P. Darling to lay out 34 residential lots on the 50 acres south of the hotel. Only five houses were built in accordance with this plan.

The roaring success of the brothers’ enterprise came to a screeching halt when there was a falling out among the brothers. Eventually it was acquired by Huntington Bay Heights Association, a venture organized by prominent real estate investor and East Neck resident Milton L’Ecluse. A succession of clubs called the casino home—the Huntington Golf and Marine Club, then the Huntington Bay Club and finally was leased to the Huntington Crescent Club. In the 1950s, the Crescent Club gave up the property and Head of the Bay Club took over. For more , see Playground on the Bay

Bay Hills

In the nineteenth century, Raymond Selleck farmed this land. When he died in 1847, his son William B. Selleck inherited two-thirds of the farm, while his brother Charles inherited the other third. William died at 54 years old in 1860, leaving behind his widow three children aged 10 and under. In 1865, Charles sold his third of the farm to William’s widow Harriet, who mortgaged the property to Frederick G. Sammis and Solomon Oakley and incurred several other debts as well. The mortgages, debts and complex questions related to ownership of the property among the family members led to William R. Selleck commencing an action against his mother. The referee’s opinion settling the dispute took up the entire front page of the April 6, 1877 edition of The Long-Islander newspaper. The referee, after determining the appropriate allocation of the debt, decreed that the entire property should be sold because it could not be equitably divided.

On July 14, 1877, the property was auctioned off on the steps of the Huntington House hotel. Frederick G. Sammis was the high bidder. He took possession in September and immediately began to improve the property. Seven months later, The Long-Islander remarked, “It is astonishing what a difference . . . lumber and paint and a great deal of hard work will make in the looks of a neglected farm.” Extolling the virtues of the site, the newspaper claimed that “The green fields, fringed with a wide strip of gravelly beach, dotted with beautiful trees, make this slope one of the finest spots in America.” Sammis commissioned Elwood artist Edward Lange to paint the restored farmstead in 1880. (A copy of the painting is posted at The Edward Lange Project)

Sammis did not hold the farm long. In 1888, he entered an agreement to sell it to Charles S. Longhurst, who assigned the agreement to George Shaw. Shaw was a partner in the firm of Aitken Sons & Co. Other partners of the firm were the principals in the Huntington Company which had developed land to the west of the Selleck farm. The old farmhouse was converted into the Huntington Bay Inn in time for the 1888 summer season (even though the property had not been formally conveyed yet).

Uphill from the Inn, Shaw built a new house, which he named “The Oaks.” The inn was removed in 1891 to open the view from Shaw’s mansion. Shaw died in 1900, and the property was sold to John Cartledge, whose family had been summering at the Locust Lodge next door since 1893.

During World War I, the Cartledge family leased his property to the Yale Unit, a precursor to the Navy air corps comprised of students from Yale University. The estate was converted into a military base with hangars, runways, a machine shop, a radio shed, and docks—although the airmen slept in the Cartledge mansion and had their meals prepared by a private chef. During the training exercises, there were a few crashes and one tragedy when a sailor was hit by a propeller he had been cranking. The engine backfired and his arm was caught in the end of the prop knocking him into the spinning propeller. He died later that night. For more about the Yale Unit, see What Huntington Did in the Great War

John Cartledge, who was president of Brooklyn’s American Linoleum Company, had died in 1910. The estate was inherited by his four children, who placed the property on the market, but it did not sell until 1924 when it was purchased by a syndicate of local investors who formed the Huntington Bay Hills, Inc. The property was subdivided into quarter acre lots. An eighteenth-century barn near the water, the Shaw Mansion, and the old water tower survive. All other outbuildings made way for new homes.

Wincoma

In the early nineteenth century, the peninsula extending between Huntington Harbor and Huntington Bay was composed of three farms. The stunning views from these properties were enjoyed by a series of wealthy New Yorkers.

Louis M. Thurston owned what is now Lower Wincoma along the shore of Huntington Harbor. He had been a broker on Wall Street. He retired to Huntington at age 32 in 1836. Here he farmed his harbor front land and became active in the affairs of St. John’s Episcopal Church. He died in 1895, a week shy of his 91st birthday.

Another tract of 16 acres along the Bay to the north of Thurston was purchased by physician Thomas Ward in 1851. He was the son of a congressman and enjoyed a substantial inheritance; he also married into wealth. Ward died in 1873.

The third tract, which was east of Dr. Ward’s property, was owned by Captain Edward Stout, a wealthy, retired sea captain.

The Ward and Stout farms were purchased by Alfred Mulligan, who in 1865 built a magnificent mansion on a bluff overlooking the bay. Mulligan was another Wall Street financier. The view from the top of the cliff looking north over the bay and through to the shores of Connecticut is “one of the finest water views in the world,” according to The Brooklyn Eagle in 1899.[xxix] Mulligan named his estate Cedarcliff.

In 1898, August and Nannie Heckscher purchased the Mulligan property and a year later the Thurston property as well. The Heckschers were two of Huntington’s most generous philanthropists, donating the park and museum that bear their name among other things (see Mr. Heckscher’s Most Generous Gift To Huntington). The Heckschers made improvements to the Mulligan mansion and rechristened the estate as Land Ends and later Wincoma.

Nannie Heckscher died in 1924. Within a year, August Heckscher sold the estate to local real estate developer William E. Gormley, who divided it into 200 lots, most were a quarter acre; some up to 2 acres. Gormley pledged to preserve the beauty of the property, especially its trees.

The mansion was purchased in 1926 by Henry R. Frost, a lawyer for the Long Island Lighting Company. He lived across the Sound in Greenwich and used the mansion as a summer home. Ten years later, during the Great Depression, the mansion was the subject of a foreclosure action. Frost and his family stayed at Wincoma for the summer of 1936 (the foreclosure was to be in May of that year). It is unclear when the foreclosure was finalized. But in November 1940, the mansion was being offered for sale by real estate broker Charles E. Sammis, Inc. Two months earlier, August Heckscher had returned to Wincoma. His friend and fellow real estate investor Charles Noyes hosted a 92nd birthday party for Heckscher at Noyes’ Wincoma house, two doors east of the mansion. Heckscher died the following April. At the time of his death, his old mansion, now owned by his friend Noyes, was being demolished.

East Point

East Point enjoys one of the most spectacular settings in the Town of Huntington.

In 1888, Dr. Daniel E. Kissam, a direct descendant of Dr. Daniel W. Kissam (whose 1795 house on Park Avenue is now a museum preserved by the Huntington Historical Society), purchased the peninsula and 10 acres of uplands from the Scudder family and built a rambling mansion

After Dr. Kissam died in December 1903, John Green, a 24-year-old millionaire owner of a Colorado mine, purchased the property. Green had the house remodeled and modernized and christened the house Point Siesta. Shortly after his wife’s death in 1911, Green sold the property to his brother-in-law James Elverson but continued to live there. When Elverson died in January 1929, he was deeply in debt. To pay the debts, the contents of the home were auctioned off, including hundreds of cases of wines and liquors bottled between 1840 and 1850.

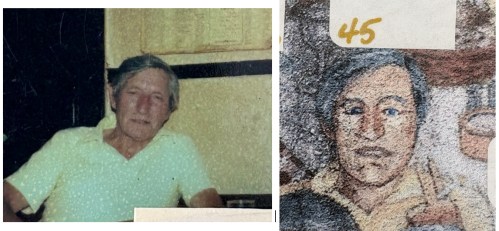

In the 1960s, Arthur and Ruth Knutson owned and restored the house. Later Gloria Smith, who owned the Yankee Peddler antiques shop, and her husband purchased the house and it was once again restored. After her husband’s death, Mrs. Smith made the house and property available for photo shoots.

The house was demolished in 2018 and a new home built in its place. For more, see No More Second Chances

Rhinelander Estate

One of the earliest wealthy city dwellers to establish a country home in Huntington was John R. Rhinelander, a doctor from a wealthy New York family who fought cholera outbreaks in New York and Montreal. Rhinelander built his magnificent mansion on a hill on East Neck between Huntington Bay and Huntington Harbor in the mid-1830s. The home commanded spectacular views as well as attention from the surrounding community.

Dr. Rhinelander was active in Huntington affairs. He died in 1857 at the age of 62. His wife Julia died seven years later. The house passed from one wealthy New Yorker to another, including John P. Kane, a partner in a large mason and building supply company in Manhattan. The street on which the house sits was named for Kane. Later, the house was owned by Frederick L. Upjohn of the pharmaceutical company and then by Thomas H. Roulston of the eponymous grocery store chain.

More recently, the house was owned by sculptor Joseph Mack and his wife, the painter Jean Mack. In the early 1970s, after Mr. Mack suffered a life-threatening car accident, the couple started the Huntington Fine Arts Workshop in their home. Five rooms in the basement were converted into sculpture studios and drawing and painting were taught in the ballroom. In 1978, it became the Huntington School of Fine Arts and eventually moved to a former boathouse on Huntington Harbor. For more, see High Lindens

Research for this post was conducted in partnership with Toby Kissam, who has written extensively on the history of Huntington Bay.

[i] The Long-Islander, June 1, 1877

[ii] The Long-Islander, March 26, 1880

[iii] The Long-Islander, April 4, 1891

[iv] The Long-Islander, June 29, 1895

[v] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Deed Liber 261, page 59. The land was held in his wife’s name.

[vi] The Long-Islander, April 7, 1882, July 7, 1882

[vii] New York Times, December 21, 1883 and February 11, 1884.

[viii] The Long-Islander, January 18, 1884

[ix] The Long-Islander, October 2, 1886

[x] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Deed Liber 300, pages 483, 487, 492 and 498

[xi] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Deed Liber 302, page 470

[xii] The Long-Islander, October 2, 1886

[xiii] The Long-Islander, February 5, 1887

[xiv] The Long-Islander, October 2, 1886

[xv] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Map No. 66, filed January 18, 1888

[xvi] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Map No. 454, filed July 15, 1897

[xvii] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 13, 1888, page 2

[xviii] New York Times, September 4, 1915

[xix] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Deed Liber 310, page 86

[xx] Suffolk County Clerk’s Office Deed Liber 56, page 120

[xxi] The Long-Islander, April 14, 1888

[xxii] South Side Signal, June 30, 1888

[xxiii] The Long-Islander, April 28, 1888

[xxiv] The Long-Islander, April 27, 1889

[xxv] The Long-Islander, March 10, 1888

[xxvi] Brooklyn Eagle, June 9, 1900

[xxvii] Brooklyn Eagle, June 9, 1900

[xxviii] The Long-Islander, September 26, 1891

[xxix] The Brooklyn Eagle, April 30, 1899, page 27

Read Full Post »